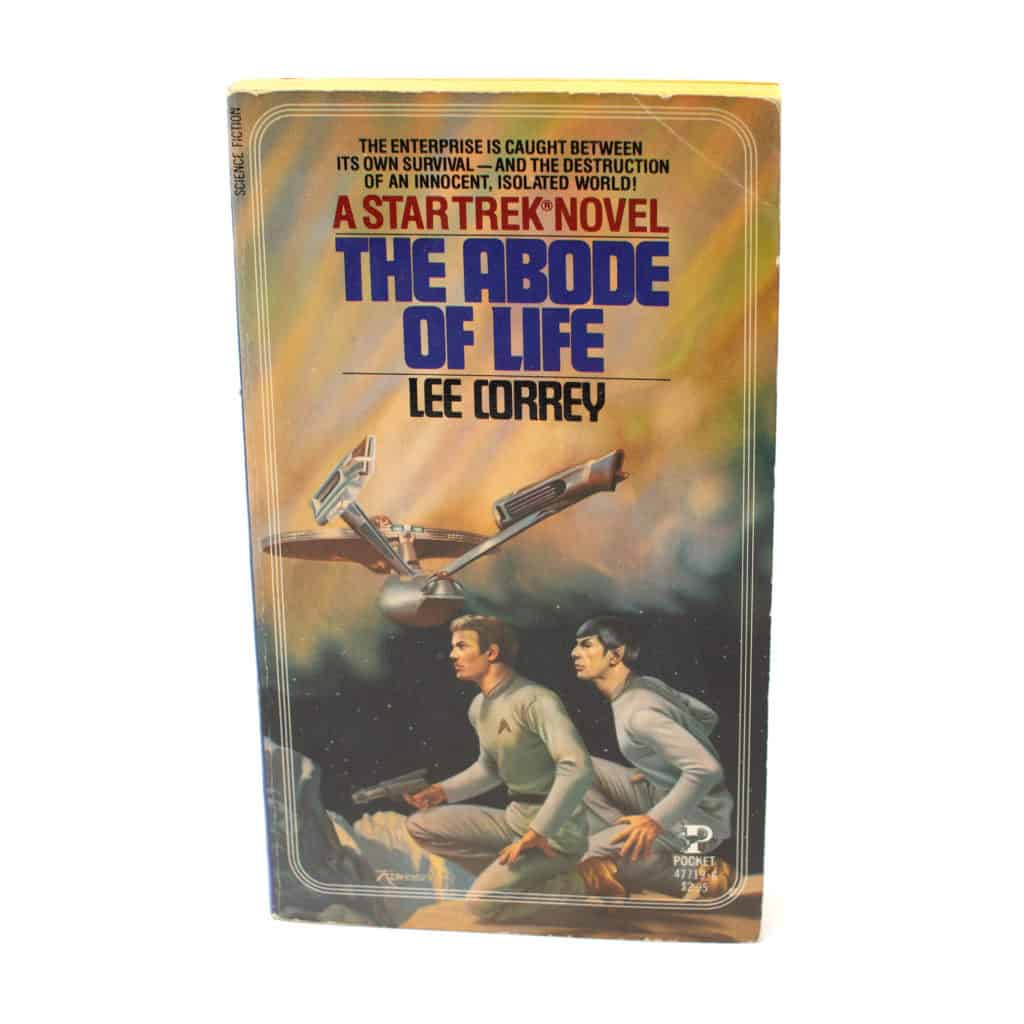

Hey, we’re back again. Strange times happening, my friends, and how better to deal with a pandemic that’s killing thousands, a President who refuses to do the most basic functions of his job, and weeks of at-home isolation than to read and then write about the next in the Pocket Books’ Star Trek novels of the 1980s, Lee Corey’s The Abode Of Life?

Have you tried alcohol as a coping mechanism instead?

More than you know.

So, here’s the back cover copy:

The citizens of Mercan cannot conceive of worlds beyond their own. Their sun, Mercaniad, is prone to deadly, radioactive flare-ups, and the Mercans have organized their life around the need to survive the Ordeal — until a strange visitor appears from out of nowhere…

The Enterprise, badly crippled and in desperate need of repairs, must seek help from a people who cannot believe in its existence. Mercaniad is about to blow, and James Kirk faces an impossible choice: to attack the sun itself and save his ship and crew — or let a people live in peace, in the only world they know…

The Abode of Life.

It just now strikes me that I should have read this summary before writing up one of my own, because it’s succinct and to-the-point.

Admit it, you did no such thing.

I will not admit it, because it’s not true! I actually sit with a real damn notepad and take notes with a pen like a damn animal as I write these, just in case I need to go into detail with these blog posts.

Uh-huh.

Sigh. I don’t need this. Not right now.

Anyway, while doing some science out in the unknown regions of the Orion Arm of the Milky Way, the Enterprise encounters a monstrous gravitic flux and is hurled across the depths of space and finds itself in a situation strikingly similar to that of the USS Voyager almost a century later1Of course, “the voyage and return” is one of the seven basic plots, sitting neatly between “a six hour phone call where you try to help your mom set up her new computer” and Barry Bostwick’s storyline in Topless Island 4 .

They discover the planet Mercan not by its radio or subspace transmissions; it has none. Instead, they follow a radiation source — the planet’s transporters. They soon discover that Mercan’s isolated position (it’s the sole planet in a system from which the Milky Way is a thin band of light an unimaginable distance away) has caused the culture to evolve in such a way that there are no transportation or communication technologies in use, just teleportation.

That’s a pretty heavy sci-fi setup, and to talk about that, we’re going to have to go back to Lee Corey for a minute.

I just Googled him and…he’s not real?

Well, he was as real as “Richard Bachman” or “Wiz Khalifa.” It’s the pen name for G. Harry Stine, a scientist, author, and leading light in the world of model rocketry. Like The Klingon Gambit‘s Robert E. Vardman, he was part of the nascent aerospace scene in New Mexico2Which it appears he left abruptly after being fired by Martin for quoting from his own book when a reporter asked him about the Sputnik launch. before starting a career as a full-time nonfiction writer and public expert in spaceflight. He become a consultant to Rich Sternbach and Michael Okuda on Star Trek: The Next Generation in his later years, earning a “thank you” in the hugely popular Star Trek: The Next Generation Technical Manual.

It’s easy to see the parallels between Stine and Arthur C. Clarke, a similarly intelligent individual who wrote non-fiction alongside “harder” science fiction with ease.

The problem with this, of course, is that Star Trek isn’t hard science fiction, and that friction shows.

First of all, I want to say there are some big ideas that I really liked :

- An entire society goes into “keeps” built deep under their oceans to flee outbursts of Berthold rays.

- There’s a cohesive creation myth on Mercan that is completely believable. My notes (see, I do write them) actually state how in-depth they are.

- The commonplace use of the transporters meant things like communicators were completely foreign to the Mercans. Why call someone when you can just beam over?3I’ve often thought that the transporter would be the best thing ever to happen to the extramarital affairs industry.

But all of these ideas (which would fit very well in something like Clarke’s Rendezvous With Rama series or Greg Bear’s Eon and its sequels) are kind of awkwardly folded and glued onto a very traditional four-act Star Trek episode structure in which:

- The disabled and storm-tossed Enterprise finds themselves orbiting a strange new world.

- A landing party beams down and discovers that there are three parties in control, each representing either keeping the status quo on Mercan (the Proctors and Guardians) or discovering the truth about the universe (the Technic).

- Kirk and the landing party try to find a way to get the Enterprise the resources the ship needs without badly violating the prime directive, even as an upcoming solar flare threatens the crew.

- Everything works out in the end thanks to the Enterprise Crew Being Very Clever.

I dunno, sounds just fine to me.

That’s the thing. With a novel, you get to do more, and it’s obvious that Stine wanted to. His style of science fiction just doesn’t work for Star Trek.

He stops the action dead in a few places to exposit quite heavily on his Very Cool Ideas while the rest of the text feels like a novelization of an unshot episode that used a lot of pre-existing sets and one new hallway, lit and photographed in different ways to try to make it look like it’s more than just a t-junction with a camera rig set in the middle.

When you compare The Abode of Life to efforts by later writers like Diane Duane’s excellent The Wounded Sky (which features a hyperintelligent glass spider bending the rules of physics to propel the Enterprise into the great unknown), Stine’s shortcomings as a Trek writer become more apparent. There’s also this overwhelming simplicity when it comes to the alien culture itself, which seems to stem from the writer’s deep belief in the free market of ideas and that laissez-faire capitalism was going to work out just fine.

Hang on, are you getting political again?

It’s not me getting political. Everything is political in some way; Star Trek even more so. Combining Roddenberry’s vision of humanity’s future with a writer who believes that the cream rises to the top leads to passages like this, which stung more than I can say with America in its present situation:

It was obvious to Kirk that Pallar was slowly beginning to open his mind. One thing for certain: Pallar was at least as intelligent as Prime Proctor Lenos. Leaders don’t rise to the top without a considerable amount of intelligence and wisdom, regardless of the culture in which they live.

My reaction:

Nobody is truly wrong in Stine’s work; they just need to be exposed to the truth, which they will quickly accept as being the right thing. It’s lazy and hackneyed and something I’ve always reacted poorly to whenever it showed up on any of the Trek series.

With a novel, you get room to explore these things a bit more and work towards an organic conclusion; this book doesn’t do that.

Okay, so give us the TL;DR conclusion.

The Abode of Life is thoroughly mediocre.

That’s what you said in the title. You could have saved yourself a lot of time here.

I know, but if I suffered, you have to as well.

Buy The Abode of Life. Maybe you’ll like it?